Petraki Monastery

Bekah and I awoke at 3:00am to (barely) catch the 3:35 bus from Syntagma to the airport. We said our farewells, and I watched my love disappear into the crowd.

On the way back, I decided to get off the bus a couple of stops early at Evangelismos (Annunciation) Hospital. Near the hospital (but tricky to find) is the ancient Petraki Monastery.

On the way back, I decided to get off the bus a couple of stops early at Evangelismos (Annunciation) Hospital. Near the hospital (but tricky to find) is the ancient Petraki Monastery.

It was 6:00am. Since it is a monastery, they were right in the middle of the morning services. I walked in during the six psalms that initiate Orthros. Read about the somber six psalms here: http://stgeorgegr.com/2010/04/the-six-psalms/

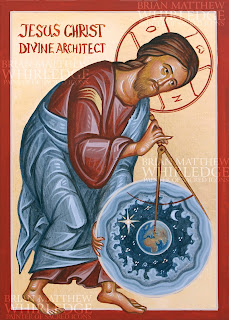

The church of Petraki Monastery is exceedingly old, pehaps a thousand years old. The easternmost half of the church is entirely covered with very old frescoes; the westernmost half is covered with contemporary frescoes in the same style (by Photios Kontoglou and his students...more about him below).

The architecture of the church is beautiful: graceful vaulted ceilings, intricate marble trim, and even several ancient columns supporting the dome, probably salvaged from a pagan temple at some point. The only unfortunate aesthetic problem was extensive electric light. While illumining the beautiful iconography on the ceilings and walls, it just seems so unnecessary and detracting in a setting like this. The architecture was designed to maximize the natural sunlight during the course of the services (vespers/sunset, Orthros/late night and early dawn, and the Divine Liturgy at sunrise).

The Divine Liturgy began. At the beginning of Orthros, there were few lay people in the church besides the monks. By the middle of Liturgy, the church was moderately full of people of all ages (including many people my age). This is impressive on a random weekday morning. The liturgy itself was very customary. The only deviation worthy of note was that the deacon read the gospel from the steps of the Bishop's throne. There was a cord tied across the nave to prevent lay people from approaching the front of the church where the monks prayed. This cord was removed only at Communion so the people could apprach. There was a memorial service following, and a yia yia offered me kolyva, which I ate on my way.

The Divine Liturgy began. At the beginning of Orthros, there were few lay people in the church besides the monks. By the middle of Liturgy, the church was moderately full of people of all ages (including many people my age). This is impressive on a random weekday morning. The liturgy itself was very customary. The only deviation worthy of note was that the deacon read the gospel from the steps of the Bishop's throne. There was a cord tied across the nave to prevent lay people from approaching the front of the church where the monks prayed. This cord was removed only at Communion so the people could apprach. There was a memorial service following, and a yia yia offered me kolyva, which I ate on my way.

I was feeling quite tired during the services, but the bread and kolyva gave me a second wind, so I decided to walk the last 2km (1.2 miles) back to my apartment. I stopped by a couple of new (to me) churches.

This church (I forget the name) is right outside the British Embassy. The architecture is nice, but the baroque iconography inside is unremarkable.

I also stopped by the tiny Agia Dynamis church, which is literally underneath a large building built over/around it. The icons are quite old and deteriorated; the only thing visible is the silver riza. An exceedingly rude woman shooed me out when she saw I was done praying and instead admiring the icons. That left a really bad taste...I might not return.

I called Arvanitis, established a time for a lesson, then took a nap.

I woke up, made a frappe, and went to my lesson, where we studied the theory and nature scales and modes. The modes of Byzantine music end on different dominant notes of the scale. The scale itself is slightly different than the even-tempered scale currently used in the west. The Byzantine scale is based on natural harmonics, so the 3rd and 7th are slightly flatter than the western equivalent. This scale was universal (and still is in most folk instruments) until the relatively recent invention of the piano and other keyboard instruments. The natural harmonics were abused so every piano key is exactly one half step (even-tempered) so that the piano could be played in any key and sound the same. Western music also used to have eight modes, and each mode actually sounded different because of the slight harmonic differences. In modern western music, only the major and minor modes remain; the other six (plus) have been erased from memory because of the emasculation of the scales in the west.

Byzantine chant is based on musical phrases, which are in turn based on the text. A natural end of a phrase in the hymn text will be accompanied by a cadence ending on a dominant note of that mode.

After the lesson, I went to a bookstore where I found a couple of great iconographic reference books. A great find is a book of Byzantine decorations by Vaboulis for adorning churches and illuminating texts.

After the bookstore and on my way home, I passed To Prodropion. Not surprisingly, I found my teacher finishing his lunch, so I stopped and we talked.

He saw my Vaboulis book and told me he has the same. Vaboulis was a student of Kontoglou. Kontoglou, in turn, was a friend of Simon Karas, who was Arvanitis' teacher.

Photios Kontoglou was trained in Paris as a artist and had great skill. On a trip to Mount Athos, he was struck by the serene and powerful beauty of Byzantine iconography. One must understand that by this point in history (early 20th century) traditional iconography had all but died out and was replaced by mediocre baroque paintings. Kontoglou studied the ancient art and brought about a revival of using traditional art in churches. Karas played a similar role in Byzantine chant in that he helped preserve and systematize oral traditions that were dying out because of the reforms of the new notation. I never knew that Karas and Kontoglou were friends. It should not surprise me, given that they were contemporaries and both sought to restore traditional forms of the ecclesiastical arts.

Kontoglou was a cantor as well, even though he did not read music, he learned by ear and oral tradition. Arvanitis says he has a recording of his chanting. I hope I can hear this sometime, as I look up to Kontoglou in many ways.

On the topic of ancient monasteries one must recommend a visit to the monasteries of Meteora. It is absolutely worth the nearly 5 hours trip on a bus. If you even have the joy to participate in a Liturgy i believe it will be something you will never forget.

ReplyDelete